6 Tips To Avoid Making Common Valuation Mistakes

Oh no… you’re the featured speaker at your department’s stock selection meeting because it’s becoming clear to everyone your highest profile stock call isn’t going to hit your price target. What went wrong? Bad valuation? Bad forecast? Or bad luck?

If it was bad valuation, this post will help reduce (or potentially even eliminate) this scenario from your future. Valuation shouldn’t be an overly complicated element in building a price target, but instead it should use the historical market psychology towards a given stock to objectively forecast where it will be in the future. Below are 6 practical valuation tips from the best stock pickers. Before covering these points, it’s worth noting that conducting valuation work is an entirely wasted effort if you don’t have an accurate financial forecast (which will be discussed in a separate post).

1. The ideal valuation multiple is not found within Excel. A more accurate valuation doesn’t come from spending hours fine tuning the risk free rate or required rate of return in Excel, but rather from understanding how market sentiment is likely to change. In terms of valuation analysis, it’s important to use Excel to analyze historical market sentiment towards a stock (discussed below) but fully understanding the current market sentiment comes from real-life conversations. Of the thousand or so buy-side and sell-side analysts I’ve had the pleasure to work with, the best stock pickers have been those who regularly speak with market participants to understand “what’s in the stock?” in terms of the market psychology. This allows them to master the art as well as the science in forecasting the optimal valuation multiple for a future price target. My key point here is don’t put too much emphasis on your detailed DCF analysis at the expense of understanding market psychology.

Valuation shouldn’t be overly complicated… instead it should use historical market psychology towards a given stock…

2. Valuation ratios (e.g. P/E, P/FC, P/S, etc.) should be relative to the market. Here’s a classic mistake I see almost daily from buy-side and sell-side analysts: “I expect the stock’s P/E to expand from its current 14x forward earnings to 16x forward earnings.” What value does this call have if the market multiple expands the same 2 points over the investment time period, like it did from mid-2013 to mid-2014? Here’s a best practice…“I expect the stock’s P/E to expand from its current 10% discount to the S&P 500 to a 10% premium.” Yes, it takes more time to value stocks relative to a broader market, but most analysts get paid to pick stocks on a relative basis, not absolute.

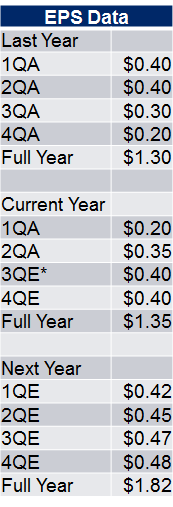

3. Be aware simple ratios can be computed differently. Exhibit 1 below shows six quarters of historical EPS and six of forward-looking forecasts (see the “E” next to 3Q of the current year) for a fictitious company. Exhibit 2 shows there are four potential methods to compute a P/E ratio for this stock, which range from a low of 11x to a high of 19x. Before accepting another analyst’s (or vendor’s) valuation multiple data, verify that’s it’s computed in the same manner that you’ll be using for your future target. Otherwise you’re using historical apples to forecast future oranges. From our perspective, options “B” and “C” are superior to “A” or “D” because they rely on rolling forward-looking estimates rather than the past (“A”) or a fixed point in the future (“D”).

Exhibit 1: Example EPS Data for a Fictitious Company

* Assume the current period is 3Q of the “current year”

Exhibit 2: Four Methods for Computing the “E” of the P/E

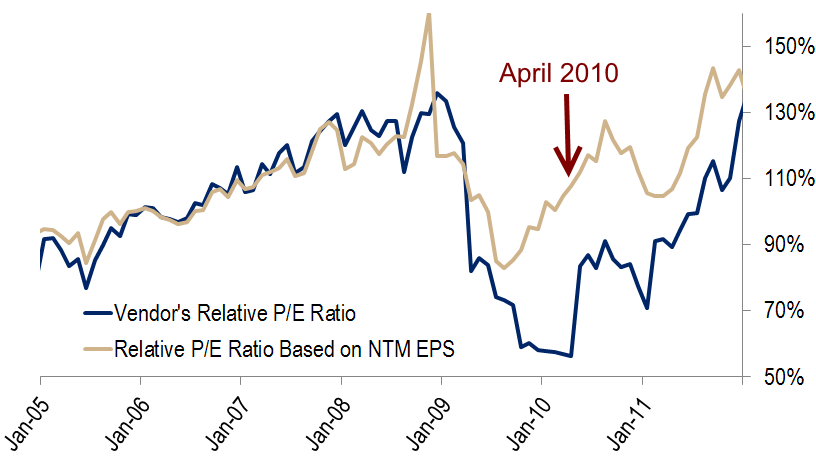

4. Knowledge of the stock’s historical relative forward-looking valuation multiple is paramount to forecasting a multiple for a future price target. Using only Exhibit 3 below, which is McDonald’s (MCD) relative P/E ratio on rolling 12-month forward consensus expectations, if we were at April 2010, would the stock appear expensive, cheap or fairly valued? Most analysts would begin by reviewing the stock’s historical peak, trough and average valuation levels in the chart because it helps to unlock the psychology around the stock. But which of the two lines is more accurate?

Stocks trade on future expectations and so looking at historical P/E ratios on a trailing (i.e. actual earnings) basis is worthless, but unfortunately, some data providers present the data this way. To solve for this see if your data service provides historical forward-looking valuation metrics (such as Bloomberg’s EQRV function), but double check the data measures what you want. For example, one vendor’s calculation of AAPL’s “Relative P/E using 12 month EPS” for the end of March 2015 is 13.9x, while the S&P 500’s P/E “using 12 month forward EPS” is 16.4x. Just doing the math with these two figures shows AAPL was trading at 85% of the S&P 500 (15% discount), but if you pull up AAPL’s “Rel P/E using 12 month EPS” from the same vendor for that time period it shows 92% (only an 8% discount).

This point is further illustrated in the MCD chart below, which shows the vendor’s relative P/E ratio (blue line) and the relative P/E ratio derived by doing the math correctly (tan line). In April 2010, the vendor’s data shows MCD trading at 56% of the market multiple while the more accurate figure was 105%.

Knowing a stock’s historical peak, trough and average relative P/E ratio (on rolling 12-month forward earnings) is paramount to understanding if the stock’s valuation is current on-trend and for forecasting the future.

Exhibit 3: McDonald’s (MCD) Relative P/E Ratio on Rolling Forward Earnings (relative to S&P 500)

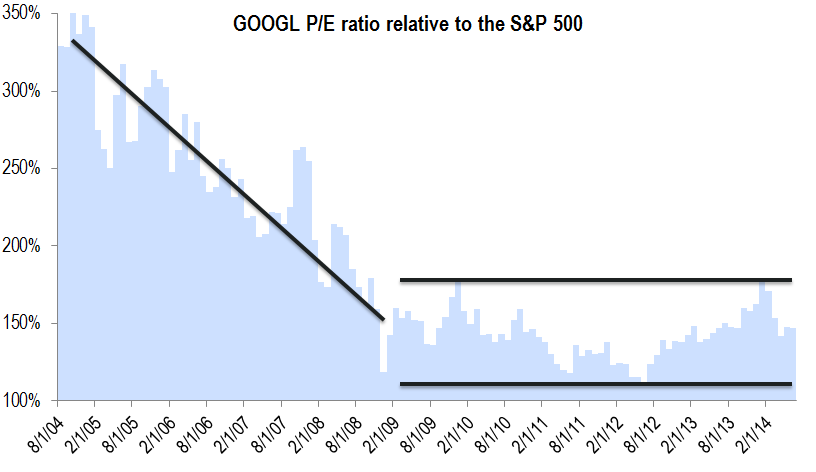

5. Don’t treat secularly-moving relative valuations the same as cyclically-moving. Looking at Exhibit 4, which is GOOG’s relative P/E ratio (on forward-looking EPS), if you were in early 2008 would it be wise to assume GOOG’s relative PE would remain at it’s historical “average” levels for the next 12 months (by just taking the mean average for the prior four years)? Probably not, because its relative P/E ratio had been contracting since its IPO, as its EPS growth rate came down from hyper-elevated levels. But if we fast forward to the end of 2014, can we assume GOOG’s relative P/E will move towards an average of the prior five years? Possibly, because the stock’s relative valuation is moving more in a cyclical pattern. The market has established a floor and ceiling for the stock’s valuation. Forecasting the future direction of a stock’s relative P/E ratio is almost impossible without knowing where it’s been in the past, especially if it’s not clear if the trend has been secular or cyclical.

Exhibit 4: GOOG’s Relative P/E Ratio

6. Develop upside and downside valuation multiples in addition to your base-case. Imagine you’re a portfolio manager and 10% of your portfolio is in a single stock that’s currently priced at $100. Three analysts want to speak to you about the stock. Analyst “A” says the stock is going to $120 one year from now. Analyst “B” has the same $120 one-year price target, but adds that the stock has a 25% probability of going to $130 and 20% probability of going only to $110. Analyst “C” comes into your office and has the same $120 price target, but explains there is a 15% chance the stock goes to $150 and 10% chance the stock drops to $80. Which of the three analysts do you want to speak with? Creating scenarios isn’t an academic exercise. Instead, it should be an opportunity to stretch your mind to think of the risks to your thesis (upside and downside) so you’re not blindsided. This goes for the valuation multiple as well as the financial forecast.

Earlier in this post I suggested that we don’t want to make valuation overly detailed or theoretical, but please don’t interpret this to suggest valuation doesn’t matter, because hopefully my points above show I take this very seriously. I want to leave you with two key conclusions regarding setting price targets: A) ensure your financial forecast (e.g. EPS, CF/S forecast) is well-researched; and B) be as objective as possible in deriving a valuation multiple, the latter of which requires a blend of historical analysis and speaking with market participants.

If you don’t have a process to keep valuation objective, you run the risk of reverse engineering the valuation multiple to build to a desired price target. Here’s one of the best quotes I’ve seen on the topic, which is from the paper “The Use of Valuation Models by UK Investment Analysts” by Imam, Barker and Clubb: “Our analysis indicates that analysts see DCF in part as a useful tool for more accurate fundamental valuation but more generally as a flexible device for ‘reverse engineering’ valuation estimates based on multiples models and/or subjective judgment.” With this in mind, follow the best practices above to keep your valuation work as objective as possible, while also appreciating that some of the valuation work will include getting on the phone and speaking with market participants about “what’s in the stock?”

AnalystSolutions offers a workshop that covers the 6 points above and many more in “Apply Practical Valuation Techniques for More Accurate Price Targets” (CFA Institute members receive 4 hours of continuing education credits), and is available 24×7 on-demand.

This Best Practices Bulletin™ targets the following activities within our GAMMA PI™ framework:

#3. Make Accurate Stock Recommendations

Visit our Resource Center to find more helpful articles, reference cards, and advice towards your growth as an Equity Research Analyst.

©AnalystSolutions LLP All rights reserved. James J. Valentine, CFA is author of Best Practices for Equity Research Analysts, founder of AnalystSolutions and was a top-ranked equity research analyst for ten consecutive years